Afrika at Louisiana

/

Afrika at Louisiana is the third exhibition of a series under the title Architecture, culture and identity that is looking at architecture and living traditions.

It opened on the 25th June and continues until 25th October.

Danish design in context … architecture, design, style and travel in the Nordic countries

Afrika at Louisiana is the third exhibition of a series under the title Architecture, culture and identity that is looking at architecture and living traditions.

It opened on the 25th June and continues until 25th October.

This exhibition of student work covers architecture, conservation, furniture design, product design, graphic and computer design and is the diploma show of the graduates this year from Det Kongelige Danske Kunstakademis Skoler for Arkitektur, Design og Konservering (the Royal Danish Academy or KADK for short).

It is worth spending time looking at the works to assess the current state of architecture and design in Denmark and to see the phenomenal talent of the students now coming through the education system here.

It is possible to identify a number of key themes - not so much in terms of the assigned project headings but more in the sense of the concerns that are now becoming a focus of attention for young architects and designers - so in architecture one strong theme that stands out was building on marginal land … particularly open or exposed or difficult rock landscape with little vegetation. Clearly, this is, in part, a response to changes in global climate where constructing settlements further and further north may become necessary as rising temperatures and lack of rain make living at latitudes closer to the Equator much more difficult but also of course young architects from Greenland and Iceland do come to Denmark for their training and the landscape that is familiar to them is very different from the green landscape and woodlands around the Baltic.

Other clear themes on the architecture side were the use of hefty timbers for framing, rather than steel, in the roofing tradition of the warehouses of Copenhagen, and an imaginative approach to using a diverse range of facing materials.

The work of nearly 150 architecture students are on display through two large halls and the projects are grouped in sections including Spatial Design, Urbanism and Societal Change, Ecology and Tectonics and Political Architecture: Critical Sustainability.

Throughout all the work graphics are diverse in terms of style of presentation but of an incredible high standard, as I suppose you would expect at this level and with CAD and high-quality printing available to everyone, but it was also good to see the continued use of models, some of amazing detail and complexity, rather than students just relying on computer 3D graphic modelling and rendering.

To the other side of the entrance to the building is a third large hall with the design exhibition of the work of more than 80 design students and here the disciplines include furniture design, textile design, industrial and ceramic design, production design, fashion design, typography, a section defined as game art, design and development and the largest group of students whose projects came under the heading Visual Culture and Identity.

I had to smile at a number of projects around cycling … only in Copenhagen eh? … but there were some incredibly sophisticated furniture designs with some work on modular furniture but it was also interesting to see the number of pieces that build on and take forward Danish cabinet-making traditions.

The exhibition is in the old smithy building on Holmen at the heart of the design schools on the south side of the harbour in Copenhagen. For visitors who do not know this part of the city, it is well worth spending time walking around the area looking at the industrial and naval buildings that have been taken into new use as this area has been revitalised over the last decade or so with the transfer of the area from naval dockyards to academic and residential use.

For details of opening times and so on go to the current exhibition link in the right-hand column of this site or see the KADK site. The exhibition is closed until 26th July for the Danish holiday but then opens until the 16th August.

I will return to the show once the exhibition re opens and will review some of the individual projects in more detail here on this site next month.

My posts through June were mostly about 3daysofdesign - a series of events that were held in Copenhagen at the end of May. Just to conclude those posts, I want to write a bit more here about one of the events … an exhibition at The Silo, called Re-Framing Danish Design, that was staged as a collaboration between Frame magazine and the new online design site DANISH™.

Two young designers, Niek Pulles from the Netherlands and Sebastian Herkner from Germany, were invited to assess or reinterpret 10 specific design pieces from Denmark that cover a wide range of styles and dates from the Safari Chair designed by Kaare Klint in 1933 to the Fiber Chair from Muuto that first went into production last year. What linked all the pieces - apart from being Danish - is that they are all still in production.

Both designers are already well established in their own studios and have a rapidly growing international reputaion - so they have clear, professional opinions about design - they have, presumably, views on how new design can and should move forward but also, as they come from neighbouring countries, they have an appropriate detachment from the Danish design tradition and from Danish design training.

The ten pieces were selected by the organisers of the exhibition and sent to their design studios.

Pulles decided to adapt the pieces by recovering them in challenging colours or interesting textures and his part of the exhibition attracted a lot of attention because these transformations seemed irreverent and possibly, for some, shocking and compounded a view that Danish design, compared to work from other countries, can appear to be too safe, too boring and lacking in humour. Pulles rectified that. The works he produced were lots of things but not boring.

Herkner, on the other hand, took a more subtle and analytical approach and for me that was actually more interesting. He worked with the pieces around in his studio and, as they became familiar, he identified specific qualities in each design and tried to appreciate what gave a sense of meaning to the designs. By sharing that process with us, through the exhibition, he also revealed something more general about how we analyse design and about how we decide which qualities and characteristics can make designs good or great or try to see which qualities explain why some designs retain their popularity.

Several of these Danish pieces are very well-known - particularly the Series 7 Chair by Arne Jacobsen - and most are widely acknowledged as good design - they have had a place in many Danish homes for many years and they are still purchased in large enough quantities to ensure their place in a current catalogue.

Clearly that in itself raises interesting questions. Do some pieces continue in production because they are acknowledged to be well designed? Is it simply because they have never been bettered? Is it because they acquire a sort of stamp of general approval or, possibly, is it just because they are familiar, they are a safe choice for the buyer?

Although it was not discussed in the exhibition, there is also an interesting insight here into a commercial aspect of design and manufacture: designers and manufacturers have to be able to distinguish which qualities in a design might generally be described as good by a professional designer but might not be appreciated widely enough to make the piece viable in commercial terms.

By placing a magnifying glass in a frame or stand with a fixed relationship to the pieces, Herkner made the viewer look at a point or area that he wanted to emphasise so each white frame holding the magnifying glass was different and each was specific to its piece and the position and the angle of the magnifying glass was fixed. A large magnifying glass could have been left free beside the object with the implication that the viewer had to look closely at the details of the materials and the construction techniques of the design but this was much more controlled than that.

In a wider context Herkner was, in effect, saying don’t take these designs for granted. Don’t just shrug and say I bought this because I like it or I bought this because my parents had one when I was little or I bought it because the design book said it was a classic. He was inviting visitors to the exhibition to really look and look carefully to see why both the design and the way each piece is manufactured is so good.

But this assessment was not just about looking at detail and appreciating quality.

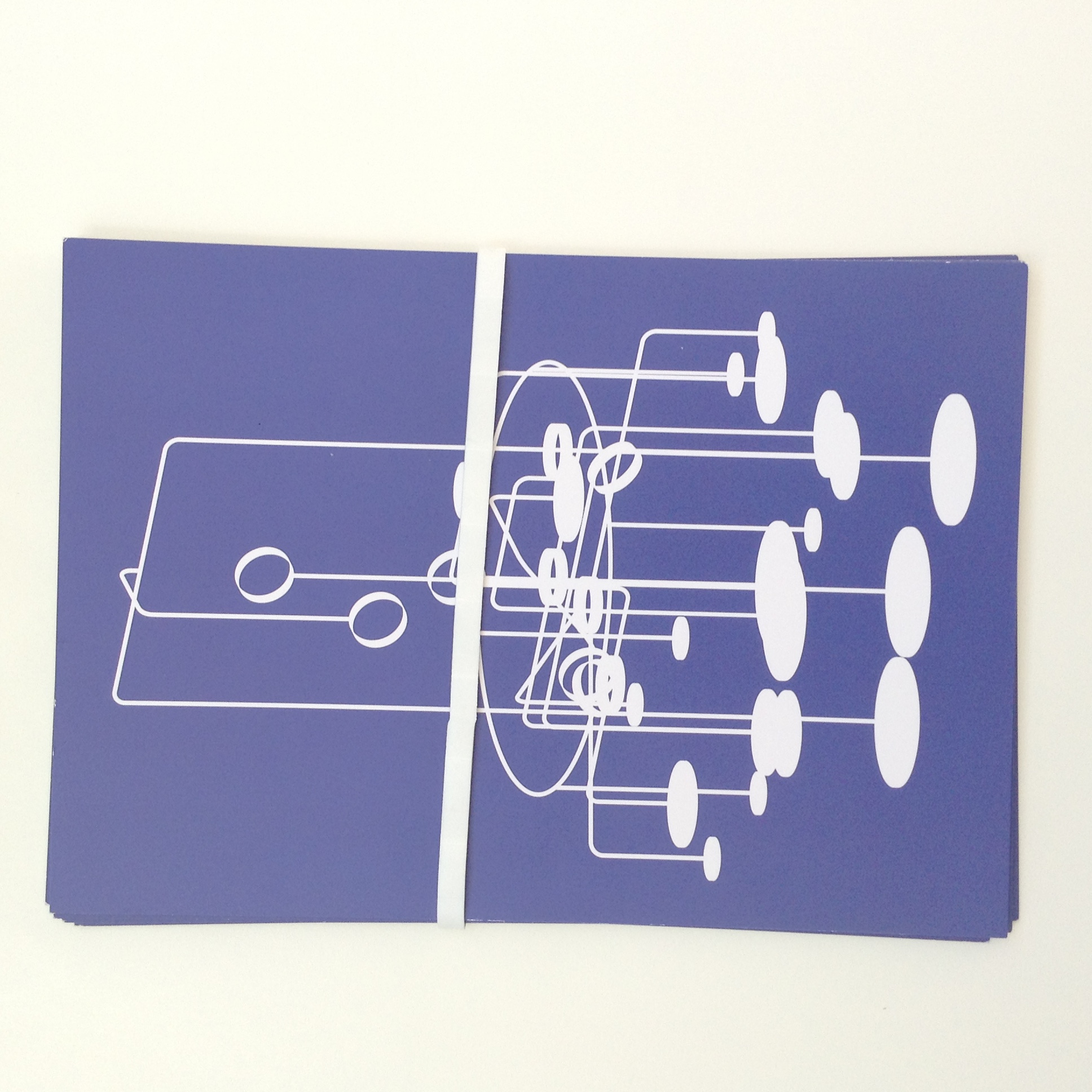

Herkner produced a set of A5 prompt cards. On one side is the framework and magnifying glass in white silhouette against a strong purple/blue and on the reverse there is a simple outline drawing of the piece and a brief summary of his reaction to the object and a single word that sums up this response and the cards were held together with a broad white rubber band. Simple but very very stylish.

There are eleven cards in the pack with the first one having a short introduction under the heading ‘Increasing details’. Then the ten specific cards are:

Through the magnifying glass, the viewer was directed to a specific feature and in some cases that explained the characteristic or definition given to the piece but in some it focused on an aspect of the piece that was actually unrelated to the word or the text. To take the Safari Chair as one example, the chair was not assembled in the exhibition and the magnifying glass focused on the brass locking nut that holds the chair together when it is in use … so a crucial but normally overlooked technical feature of the design rather than something ‘poetic’ and for the chair by Borge Mogensen the magnifying glass was focused on the woven seat and that appears to comment on texture or the use of materials but, in fact, the card explains that several years ago Sebastian had visited a paper mill near Barcelona where paper cord for seating is made and this formed, for him, a personal connection with the work.

I confess that I was slightly confused when Herkner, in his introduction, emphasises that these ‘ten characteristics are interchangeable.’ Although I can appreciate that, for instance, the Safari Chair, if seen on a theatre or film set for Out of Africa is merely using a period piece in a poetic way but on an urban balcony in Copenhagen might be ironic but it could never be described as simple or six Muuto chairs around a dining table become modules and are functional but have nothing to do with mobility.

What is important is that Herkner is recommending careful observation and careful analysis of the object in reference to our normal criteria for assessing a design - its function, its aesthetics, its use of materials, the technical details and so on - but he also wants the viewer or user to analyse their own reaction and interact with the piece.

So what at first appears to be clinical … what could be more clinical than a magnifying glass? … rapidly becomes an analysis of our emotional reaction to the design and our connection with a piece. So this then becomes a very personal interpretation of the term reframing for both Herkner and for the visitor to the exhibition.

My only real criticism is that this might be seen as an academic exercise by a designer for designers. He excludes any form of judgement or opinion - which you might expect if design works are given art gallery status under a spotlight - and there is no context if these are to be seen as readily available product pieces that anyone can buy. I’m not complaining about that but it was interesting that no attempt was made to assess how these pieces are used either individually or together so where and how does the buyer fit in?

Someone could move into the Silo - in the space above the exhibition - when the new apartments are finished and purchase all these design pieces. It’s possible. So, how would they work together? Would they show the buyer had a clear appreciation of good design? Would it be tasteful or slightly odd to have a Safari Chair alongside a Montana shelf system? Well it all depends on the colours chosen and if the Safari Chair was used as a focus/discussion piece or if, maybe, it had been inherited from the family and was clearly well used and well loved. Or would putting these objects together, even theoretically, be seen as a cautious approach to design, buying only what is recognised or generally accepted as good design?

Sebastian Herkner raises some incredibly important questions and ideas about design in general but specifically about how we respond to good design and how important it is that we analyse and try to understand that reaction.

Next month, there will be another opportunity to see the exhibition at Northmodern at the Bella Center in Copenhagen from the 13th through to the 15th August.

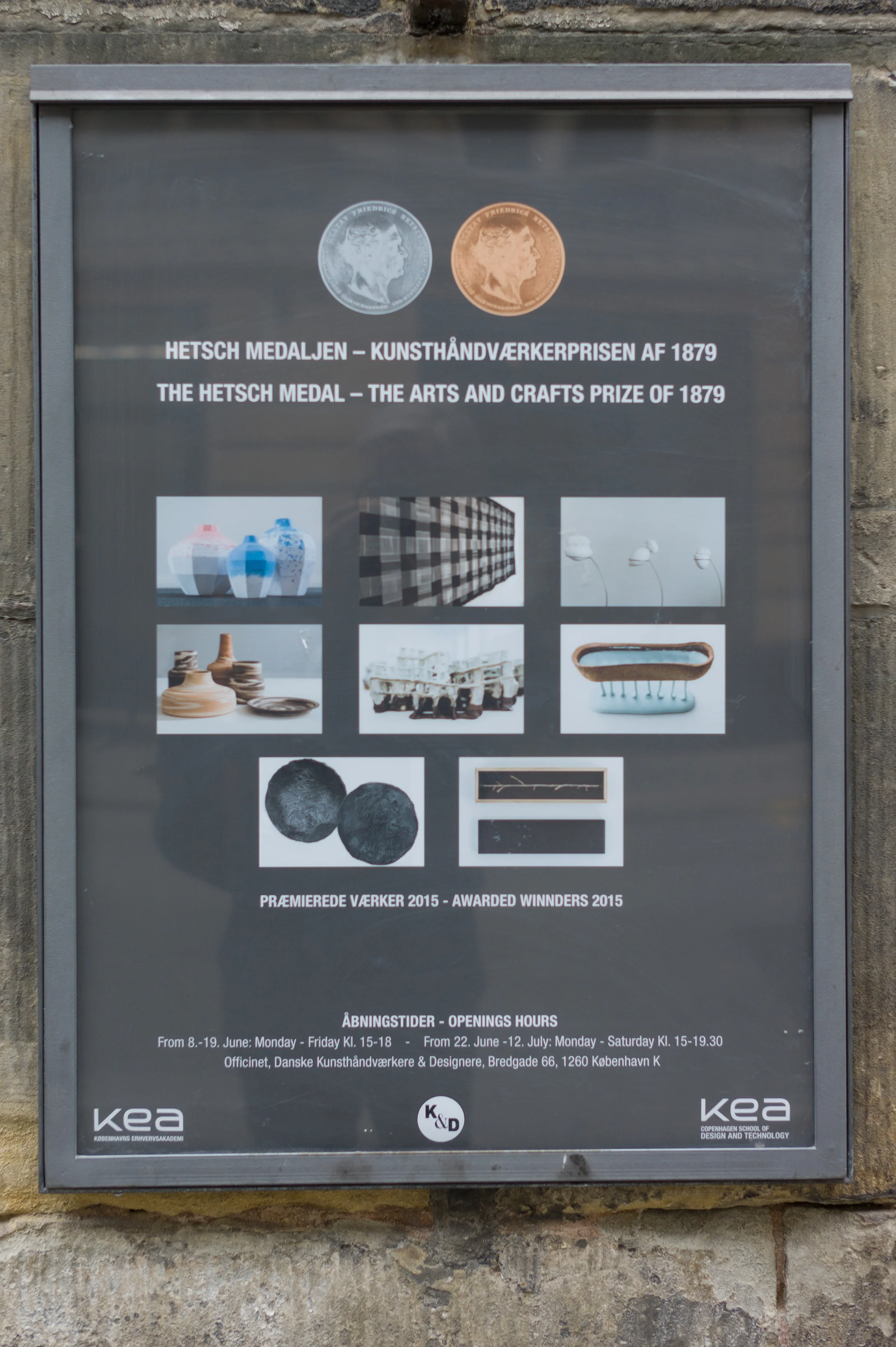

In April I posted about an exhibition in Copenhagen at the Superobjekt Gallery of work by the textile designer Vibeke Rohland. In May, at Copenhagen City Hall in the presence of Her Majesty Queen Margrethe, Vibeke was awarded the prestigious Hetsch medal - a major Arts and Crafts prize awarded first in 1879 and now hosted by kea - the Copenhagen School of Design and Technology. This year the award committee included the artist Björn Norgaard, the architect Kristin Urup, the museum director Bodil Busk Laursen and As Øland from Dansk Fashion and Textile.

Works by the winners of medals are now on display at Danske Kunsthåndværkere & Designere, Bredgade 66 and the exhibition continues until 12th July.

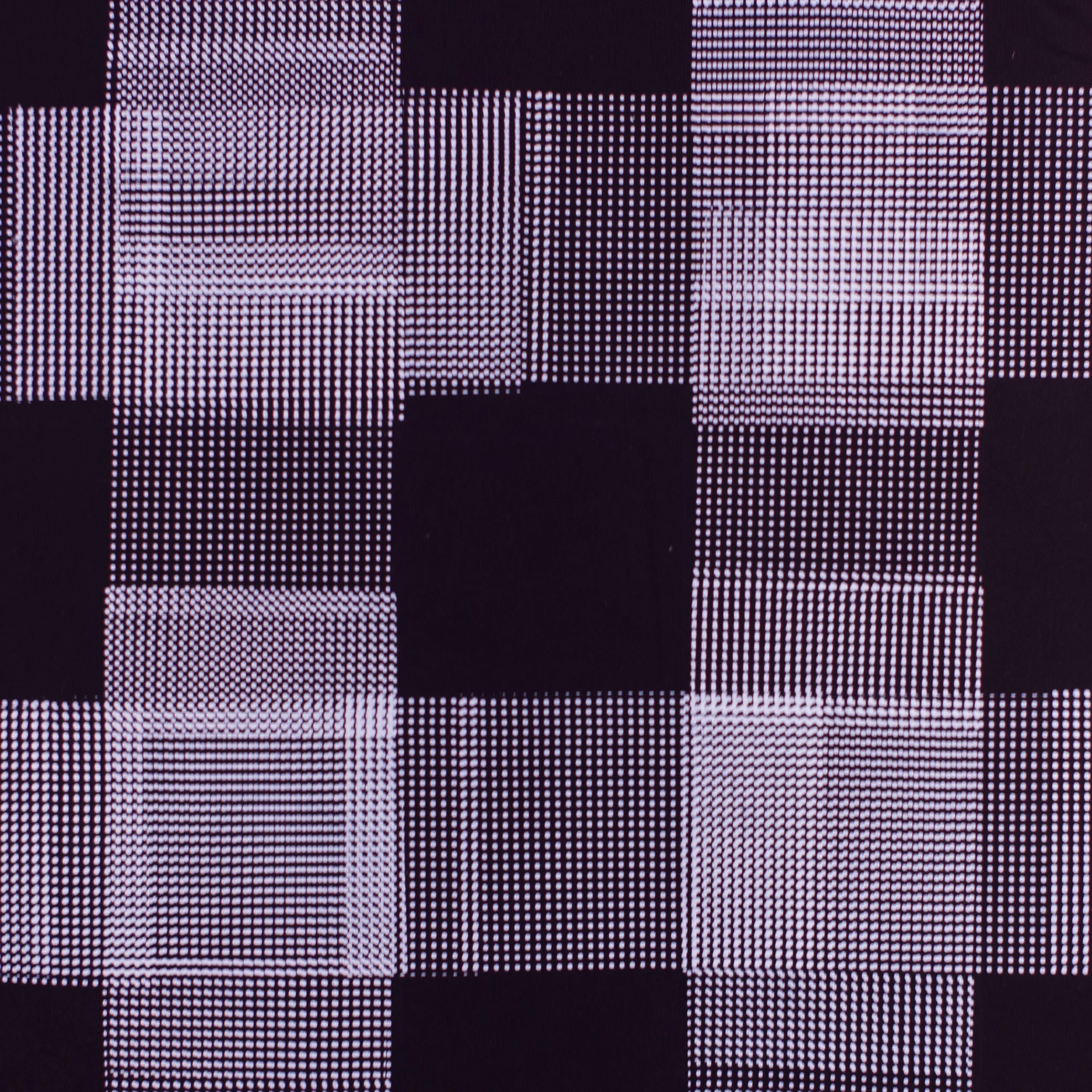

The striking and very impressive winning work by Vibeke, Crossroads’n Ginham, is a silk-screened piece in white on a rich black. The starting point for the piece was an exploration of the well-known gingham pattern which is a traditional woven textile with a tight regular pattern of small squares - often white on blue, white on red or white and pink. Gingham is woven in a light or medium-weight cotton; the finished textile is double sided and because it was light and strong as a fabric it was often used in the USA for clothes for children or for table clothes and curtains … think Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz and picnic baskets.

In contrast, the work by Vibeke is printed, single-sided and forms a substantial hanging with the weight of a tapestry with incredible visual strength and impact; gingham is a tight repeat of squares and this piece by Vibeke is actually a design without repeats although the pattern seems at first to be quite regular and where gingham has tight small squares, that together often form larger checks, close examination of this piece shows the design to be made up with small regular dots of thick, almost impasto, layers of white dye … so, as in other works by Vibeke, this is, if textiles can be subversive, subversive. It’s a very very clever exploration of tight texture with layers of pattern to give visual richness and layers of print built up to give a strong sense of depth … an exploration of a traditional textile technique to take it forward in a striking new form.

The works by the other silver medallists are on display and include pieces by the ceramist Charlotte Thorup, brooches by the goldsmith Janne K Hansen and an elegant and finely-made piece in wood by the cabinet maker Kristian Frandsen along with works by the winners of the bronze medal.

This exhibition was a collaboration between DANISH™, the web site of the Danish Design & Architecture Initiative that was launched last November, along with FRAME, the design magazine and ten Danish manufacturers.

Two young designers, Sebastian Herkner who studied in Offenbach am Main in Germany, and now has a studio there, and Niek Pulles who trained at the Design Academy in Eindhoven but is now based in Amsterdam in the Netherlands, were asked to take ten Danish design works as a starting point and, in any way they saw as appropriate, to make their own assessment or their own interpretation or their own translation of Danish design.

The design works for each of the designers were:

Tray Table, designed by Hans Bølling in 1963 and produced by Brdr. Krüger

Plateau, a new low side table by Søren Rose Studio for DK3

Caravaggio pendant light, by Cecilie Manz with the first version in 2005 for Lightyears

The Montana storage system from the company founded in 1982

Nordic Antique, a range of hand-painted and printed wallpapers by Heidi Zilmer

And there were 5 Chairs:

Series 7™ Chair, by Arne Jacobsen from 1955 and produced by Fritz Hansen

The Tongue Chair, by Arne Jacobsen from 1955 and produced by Howe

Chair J39, designed by Børge Mogensen in 1947 and produced by Fredericia Furniture

Safari Chair, designed by Kaare Klint from 1933 and produced by Carl Hansen & Søn

The Fiber Chair, designed by Iskos-Berlin and launched last year for Muuto

Both designers are building rapidly their own International careers - so both have a clear view of how the design industry is moving or should move forward but also have the perspective of someone within the profession but from neighbouring countries that have their own strong design traditions so they could be more detached in their assessment of Danish design than Danish designers.

Sebastian Herkner focused on the details and the quality of finish found in all the pieces by suspending large magnifying glasses from simple and elegant white-painted metal frameworks in front of the pieces. Each identified a different character or quality that had been observed as the works stood in the studio. Danish buyers demand extremely high production qualities but this is now taken as a given but the magnifying glass forces the viewer to focus in on pieces that, on the whole are so well established and so familiar, they rarely excite comment. In part this view also shows that simplicity is achieved by refining the elements until nothing can be added or taken away without compromising the integrity and beauty of the whole. With such a perfect starting point, or base, it is then the way that the owner uses the pieces that add individuality and personal history.

Niek Pulles took the opposite view, adding to the pieces himself, particularly adding texture but also pattern and colour. This hastened the time process by which families might add to and adapt the pieces to make them their own. One very marked and interesting difference was in the way the two designers approached the wallpaper by Heidi Zilmer. Although the tile version looks like a simple grid of dark lines over a uniform grey representing small square glazed tiles the magnifying glass showed the huge skill of the trompe l’oeil painting of crizzled glaze and irregular grout, here a deeper complexity than the apparent simplicity, whereas Niek Pulles used laser cutting to create new fine geometric patterns through the papers which were then overlaid to emphasise the way the papers themselves are built up through complex layers of paint and gilding.

This is a major and extensive survey of design for children, progressive Nordic design, that includes examples of furniture, toys and books for children, clothing, photographs of school architecture, playgrounds and public spaces, along with posters and advertising. There are a few references to food and packaging with the OTA oat flakes and tetra paks for fresh milk for children and even a three-wheel Christiania bike from the 1980s with its large square front box for carrying small loads of goods or large loads of kids.

The title of the exhibition comes from a book, The Century of the Child by Ellen Key, that was published in Sweden in 1900 and was where Key wrote about child labour, which then existed throughout Europe, and wrote about her concerns about poverty, social conditions in working-class homes and the need for health care and support for young mothers.

Really the first main gallery sets a theme that runs quietly through the exhibition … from the start of the 20th century there is furniture from a middle-class nursery and illustrations from the book At Home by Carl Larsson. These show the life of children from affluent well-established families who had the freedom and opportunity to play and their rooms and gardens are filled with colour and toys. It was this freedom to play that Keys advocated for all children and it was the Key’s vision that all children in Sweden would have a childhood like that shown in A Home.

There are other important political points made in a number of explanation panels through the exhibition … so for instance the Nordic countries were amongst the first signatories to the United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of the Child and in 1974 Sweden was the first country to introduce parental leave for men … not hectoring political points and presented in a fairly subtle way but certainly important and certainly appropriate for wider ongoing debate.

Distinct themes make the exhibition incontestably Scandinavian: many of the designs and objects have obvious connections with nature and natural materials and another theme is a strong and well-established sense of society in Nordic countries and how this effects the lives of children … both the role of society in providing appropriate support for children and parents but also ultimately, in return, the role of the individual in society as they become an adult. Over the century there was also a growing awareness of the importance of free play not simply for the sake of play but in giving a child every opportunity to develop as a person.

The book accompanying the exhibition makes a crucial point that I had not thought about, even though I consider myself to be a social historian: it points out that the battlefields of the First World War left millions of widows and fatherless children and was followed closely by the Depression of the 1920s so “… high unemployment and growing concerns about low birth rates: and the lacking quality of life for the general population … children were the literal and symbolic promise for a better future.” This was an imperative that drove planners, architects and designers to improve schools, homes, toys and equipment for learning and for play.

Some things shown here are relatively obvious: good toys are robust and simple, or at least not unnecessarily complicated or fiddly and are best in bright colours. A prime function is to stimulate the imagination but not direct it. For international visitors, the most readily recognised are the wooden tracks and trains from Brio of Sweden and Lego, of course, and wooden animals and figures by Kay Bojesen from Denmark.

Furniture produced from the middle of the century onwards is not simply scaled down from the furniture made for adults but often takes innovative and imaginative forms. There is a chair from Trip Trap that was designed by Peter Opsvik in 1972 that can be adjusted to raise a child up to the eye line of adults sitting around a table on normal chairs so the child is not looked down on. From Artek there is the Baby High Chair from 1965 and a number of pieces from IKEA.

Special school furniture becomes increasingly important and also of course the importance of good, high quality design for building new schools.

As with toys so with school buildings, the most obvious changes in the design of schools was in the furniture and in the introduction of strong colours and an emphasis on furniture that was well made and could be easily maintained but there were massive changes in the number of rooms and the diversity of spaces and areas that were not traditional classrooms.

An amazing group of new schools were designed and built shortly before the Second World War. Skolen ved Sundet on Amager in Copenhagen was a traditional school but it also had facilities for sick children with a large upper room with windows that slid back so they could rest but benefit from sun and fresh air - this was a period when tuberculosis was still common and had a terrible impact on children and their families. The school was an early building in reinforced concrete … In the catalogue Anne-Louise Sommer describes it as a functionalist masterpiece that “represents the very core of democratic, inclusive architecture, with its distinct focus on helping the weak. In this sense, the architecture reflected the prevailing ideals of the emerging social democratic welfare state.”

Eriksdalsskolan on Södermalm from 1938 by the architectural partnership of Nils Ahrbom and Helge Zimdal was one of the largest and most modern schools of the period with a pool and sports hall, a library and its own cinema.

Inkeroinen School in Anjalankoski from 1938-39 by Alvar Aalto was on a sloping site with classrooms at the upper part of the site but also workshops and significantly a large gymnasium lower down. Developing physical strength and good overall health became increasingly important as a role where schools could and should intervene.

Major changes in the way schools were laid out began in the inter-war years but perhaps the most rapid developments and changes are in the 1950s and 60s and onwards.

Again there is a political point here. In part, so much money and thought was given to improving education because education and the development of technical training, even at school level, were important in the Cold-War period … there was a fear that western Europe would drop behind the Soviet Union in what was seen as a race to develop industry and technology. In my own secondary education in England we were not taught French and Latin as had been normal in grammar schools but German and Russian as the the languages of science and the future.

There are photographs and information about a number of playgrounds as the provision of play equipment in public parks and gardens was seen as more and more important. Skrammellegepladsen … the Junk Playground in Emdrup in Copenhagen dates from 1943 and was what in England, in the late 50s and 60s, was often called an adventure playground. Again the idea was to encourage a sense of independence where children could develop physical skills from climbing trees and building surprisingly large constructions. Not much worry about Health and Safety inspectors back then.

From much more recently there is a model and photographs of the Puckelball Pitch from Malmö … an amazing football pitch on dramatically undulating ground with mad bent and twisted goals of different sizes to even out skills of sides with children of different ages and different abilities.

In the exhibition area there are some interactive sections with, for instance, a room where children can create stop-start animations with wooden toys; there are two areas with foam floor toys for toddlers from bObles and many of the cases are provided with wooden steps so children can climb up to look but generally this is an exhibition for adults with a lot of text - that really does merit and justify time spent reading and absorbing - and should be a must-see for teachers and educational administrators along with young parents looking for ideas and context … and of course for old adults just wanting to reminisce.

Throughout are reminders of the political background and the social changes driven by new political philosophies. In school building “no expenses were spared for working-class children in the era when the social democrats governed the entire Nordic region and were intent on building the welfare state.”

A strong theme is the complex idea of using design to encourage children not only to develop their imagination and creativity but also the need to encourage children to play together and to be active for good physical development … now a significant problem again with growing levels of obesity.

Health is also covered in the exhibition in terms of protecting the child so for instance there are early car seats.

Theories about best practice and ideas of using good design and good architecture to intervene in child rearing extends to the design of housing. The Collective House on John Ericssonsgatan in Stockholm from 1935 had 57 apartments, a restaurant, a central kitchen, a central laundry and a department for child care. Apartments had minimal kitchens but dumb waiters so food could be ordered and delivered from the main kitchen. Here, it was clear, the responsibility for child rearing was to be shared between the parents and the state. The state felt it could and should help and direct and support every stage of a child’s life … the Finnish Maternity Package, providing much that a new baby would need including clothes and nappies, started in 1937 for eligible families but the scheme was soon extended to go to all mothers to be.

Century of the Child is extensive and rightly thorough for it charts the phenomenal changes that have taken place in the life of children in the Nordic world over the course of a century and with these huge changes and developments, designers and, through them, the design process was central. “This is design, architecture and art created for children - not just adapted adult versions.”

The conclusion is that “Thoughtful design, architecture and art have … become part of children’s everyday life - not a privilege for the few, as they were 114 years ago.”

for more photographs of the exhibition

Museum Vandalorum, Värnamo, Sweden - 10 May to 28 September 2014

Designmuseum Danmark, Copenhagen - 28 November 2014 to 16 August 2015

Design Museum, Helsinki - 9 October 2015 - 17 January 2016

Until 16th August, there is an exhibition of modern jewellery in the small gallery between the entrance hall and the restaurant at Designmuseum Danmark.

There are 153 pieces on display in a wide range of styles and a wide range of materials .... works by leading experimental jewellery artists in Denmark. They are from the collection of the Danish Arts Foundation and have been purchased over the years since 2007.

They are shown in a new group of cases called ICECUBES, designed by Søren Ulrik Petersen.

Jewellery from the Danish Arts Foundation's Collection, Designmuseum Danmark, Bredgade, Copenhagen

The exhibition of works by Peter Doig, at Louisiana Museum of Modern Art until 16th August, includes many large paintings and is displayed in the set of galleries that run under the main central lawn of the museum.

This is one of the Alice-Through-The-Looking-Glass areas of Louisiana where, after a series of rooms beyond the museum shop, you come to a wide and well-lit staircase that spirals down to a series of curved corridors and very large gallery spaces where there is little that gives you any sense of direction. At the end of the series of rooms is a matching spiral staircase, in grey marble, and ascending you find yourself on the other side of the garden, now outside the restaurant.

During the week, from Tuesday through to Friday, Louisiana is open until 10pm. The sculptures in the gardens around the gallery are amazing in the evening light and it is possible to have supper there and sit on the terrace looking out over the sound to the Swedish coast. A pretty civilised way to enjoy a long warm Danish Summer evening.

Copenhagen now houses 30% of the population of Denmark and the city is growing rapidly with 1,000 people moving here every month. Obviously there is a huge pressure to build new housing and with that pressure there is a very clear understanding by politicians, planners and architects that they have to get the new developments right.

An introduction to this exhibition at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts puts the problems succinctly:

“The strain on the city leads to rising prices of land, and high construction costs lead to higher costs of accommodation, both in new build and renovated properties. This makes it difficult to build in general, and almost impossible to build cheaply ….. The city is being segregated into enclaves, with wealthy people in attractive, but expensive districts ….. while citizens with lower incomes have to settle in less attractive districts of the metropolis. This is a threat to social welfare and cohesion.”

But, as with the recent exhibition at the Danish Architecture Centre about the problems developing with climate change, The Rain is Coming, this is neither a reason for doom and gloom nor an excuse to do nothing but talk anxiously about how awful it all will be. Rather, work has already begun on a massive amount of new building in the city … this exhibition is about housing schemes well on in the stages of planning so either where building work has started or is imminent. The contrast with the UK could not be greater: although both countries have been through the same economic recession, politicians in England seem to talk endlessly about the lack of housing but do nothing while in Denmark there has been a massive investment in infrastructure and work is progressing to build homes all round the city. And this is not small-scale development. The new area of Nordhavn is in part on land that was industrial dockland and in part is claimed from the sea but this area alone will have homes for 40,000 people and places for jobs for 40,000 people.

Planners and politicians in Copenhagen are no longer at the stage of prevaricating, umming and ahhing and trying to decide what they might do, if they ever were, but clearly, from this exhibition, work is well in hand and now they are making sure that they do it properly.

The drawings and plans also bring out clear themes. In Copenhagen the housing type with apartments around a courtyard is well established and clearly successful so for the future, particularly in the inner city areas, that building type predominates although some tower blocks are proposed in some developments to ensure necessary density.

Balconies, terraces and roof gardens are important for private outdoor living space but there is, in all the schemes, a focus on the importance of common space of a high quality and emphasis on appropriate vegetation and the importance of water not only as a leisure facility, but as an important visual foil to the hard landscape and as a major consideration when dealing with the increased amounts of rain predicted for the region.

There is also a clear emphasis on the use of high quality but appropriate facing materials so building with brick and timber but also using concrete to reflect the industrial heritage of many of the areas being developed. Large windows, light and good views out are priorities and there also seems to be a much more generous allowance for space in the individual housing units than anything seen in new housing in England.

The schemes also include housing in outer suburbs with, for instance, the plans for Vinge, a new town north of Copenhagen that will cover 350 hectares and will be the largest urban development in Denmark.

Many of the drawings for these proposals included children playing in meadows and gardens or families on bikes or in canoes. In most other countries that would be artistic licence but in Denmark gardens, public spaces and exercise are not optional extras. Honestly. Look at my photographs taken wandering around Nørrebro just two days ago and when I moved here last summer one apartment I considered renting was unfurnished except for a well equipped terrace and two canoes. As I said to friends … only in Denmark.

The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Schools of Architecture, Design and Conservation, KADK, Danneskiold-Samsøes Allé 51, Copenhagen

Continues until 14 May 2015

This is a significant and inspiring exhibition at the Danish Architecture Centre in Copenhagen that is primarily about the importance of community involvement at all levels in our cities - from making them really work day to day at the street or district level right through to being involved in major planning decisions.

The introduction panel sets this objective out very clearly … the “right to form our cities is something special. It is a product of a political development, but also the result of idealists all through history having challenged what and how a city could and should be - even when it was not formally possible. Citizens have come up with good ideas, gained support and fought for a better city. And not out of a sense of duty, but because they simply can not help themselves. They want to make something of their city, and they would like us to be part of that journey.”

This is very much an exhibition for the digital age in which we live: an exhibition about ideas - rather than a gallery exhibition about beautiful objects that you simply admire. There are no objects as such here but bold and, in some cases, provoking quotations from planners and politicians; information panels about specific community projects and plenty of audio visual screens where you can listen to interviews or commentaries about specific community projects.

As someone trained in museum work it was interesting to see how all this material was deliberately presented in a way that might not work in a printed book or, particularly, how it might not work if it was simply out there in the data world on a web site reached through a url. Here visitors are encouraged to explore but there is never-the-less a clear sense of a route or progress through the material that you still cannot really control as people click and move around or quickly click on from an on-line site.

There are information panels about a wide range of community-led projects including Østergro - the community gardens of the Østerbro area - the community shared ownership scheme of Den 3 Revle - the Third Bar - in Nørrebro and the Restaurant Day project. There were also a number of international projects shown here including the amazing project to paint the houses of the Rio favelas, the success of the High Line in New York and the project to convert car parking spaces into community parks for a day with people moving in fake grass, plants in tubs and seating to reclaim a stretch of kerb.

There are significant planning projects here - for instance trying to involve as many people as possible as Odense grows rapidly from a small city into a major conurbation.

Some information surprised me … I had not realised that community involvement in planning has been enshrined in Danish law since 1970.

All the main panels are in English as well as Danish so with no Danish I could follow everything well but where I missed out of course was my usual trick in a museum of listening in to the conversations of other visitors to work out just how they were responding to what they were looking at to find out if they were inspired or if they disagreed.

The last section of the exhibition has information about Borgerlyst (Citizen's Desires ?? ... wishes sounds rather feeble and wants too needy as a translation) set up by Nadja Pass and Andreas Lloyd to use their experience from various community schemes to encourage and nurture action groups and there is a long table with benches on either side that takes you through a question-and-answer sequence to see if you have an idea for a community project and to encourage you to take it forward.

There are a large number of events associated with the exhibition and the last wall has bright bold graphics setting these out with tear-off strips for contact telephone numbers.

Even in Denmark there must be rapacious developers whose primary aim is profit and there must be politicians or administrators reluctant to relinquish power or influence and of course there are citizens who don’t have the time or the energy to get involved or feel slightly in awe of officials and think that planning or decisions about architecture and redevelopment in their city should probably be left to the experts but my strong feeling is that, here in Denmark, that gap - between wealth and power and the majority of people who actually live and work in the cities - is actually smaller and more easily bridged than in most cities in the World.

My only real concern is just how wide an audience will Co-create reach? I can see that actually having the material there and visitors having made the effort to travel to the Centre they want to focus on the material. But the number of visitors seemed relatively small and were all the usual suspects - trendy middle class families, men who were clearly architects and designers and a good number of students presumably studying architecture or design. How do you reach a wider demographic with something as important as this?

Having said that, special events held around the building and on the quay outside have clearly been well attended.

But overall it really is inspiring to see how many people have become involved over such a wide range of projects and have made a substantial and real difference to their urban environment.

The exhibition continues at the Danish Architecture Centre in Copenhagen until 7 June 2015

An exhibition in the upper gallery of the Moderna Museet in Malmö that is showing the work of eleven artists who have produced videos that explore the sense of isolation and alienation that people feel as the World changes rapidly through wars and with migration from the countryside to the city or from one country to another in pursuit of work.

Many of the videos have a strong political or social and moral stance, and are more powerful and important for that, but this is primarily a design blog. However, the series of three videos from Cao Fei and the accompanying interviews, collections of photographs and some installation artefacts brought me up short for the points it made about the design World.

Whose Utopia, My Future is not a Dream and What are you doing here? were filmed in the Osram factory in the Pearl River Delta in 2006.

One film shows workers strangely and awkwardly frozen in a pose … the artist has clearly asked them to hold the pose without explaining why and there is no speech but in that slightly embarrassed pause, as work carries on in the background, you see faces begin to look worried or look quizzical or look frustrated and in the stretched-out wait you see simple differences that make these young migrant workers all incredibly different.

There is a dream-like sequence with dancers, some performing western ballet movements, and this represents some of the aspirations or hopes of these people who have left parents, spouses, children and familiar homes for the draw of regular salaries.

What is heart-wrenching is the photographs of the worker’s dormitories where they have created small personal sleeping spaces on huge shelves of Dexion racking and pallets with their personal possessions - the cheap versions of the luxury goods other Chinese factories are making for the west like carry-on cases with wheels when they are going nowhere - and many have toys, which emphasises just how young many of these workers are, and there are posters of western celebrities including football stars to show their hopes for something different from life.

Just what is the real cost of the design goods we import?

On Friday 24 April an exhibition opened at the Form Design Centre in Malmö with drawings and models by 25 architects for garden pavilions, log cabins, a mini villa and even a triumphal arch that were all inspired by a change in Swedish planning laws from the Summer of 2014 which now allows for the construction of buildings without requiring planning permission if they are 25 metres square or less and have a ridge height of 4 metres or less. These buildings are called Attefallhus after the housing minister Stefan Attefall who took through the legislation.

In many countries in northern Europe there is are strong, well-established traditions for building compact, semi-permanent buildings that can be used for living in for a few days or longer in the summer from mountain huts used by farmers practicing transhumance, to substantial garden buildings on Dutch allotments, or small summer homes by the lake or sea shore, including beach huts in England, although these are rarely used overnight.

However there is now growing pressure for compact, well designed permanent housing for other reasons.

With climate change and political upheavals there is huge pressure on resources. Clearly the primary human rights are for food and water and then for freedom but with the mass migration of people from the country to the city and from one country to another in search of work the next most important human rights are presumably for light, clean air, space and secure domestic accommodation. As land becomes more expensive and in big cities scarce, there is clearly huge pressure to design and build compact domestic accommodation.

Obviously, the schemes shown here in the exhibition are from and for an affluent European country and clearly some of the buildings are pure follies and some are designed for the new ‘pressures’ felt in first World countries to provide self-contained accommodation for children if they return home after university or for elderly parents to move into or even for guests. But many of the ideas shown here could be used for effective temporary accommodation after natural disasters or to cope with mass migration to escape war … after all these ideas are in many cases about managing to fit self-contained accommodation into as small an area as possible.

In fact, many of the ideas for specific details could be used in compact houses and apartments anywhere … for instance narrow doors that concertina back to give easy direct access to a terrace and shutters that hinge upwards to create a clearly defined outside space to make the small interior space seem less constricted.

A log cabin or hide, Arvet from Trigueiros Architecture, has a very clever arrangement where the plan and arrangement of furniture is neatly square … the tight use of neat geometry is one way to keep a space appearing to be larger than it is … while the logs or timbers forming the sides of the building are laid at a slightly different angle at each stage to form a spiral. Windows have a deep reveal that respect the floor plan in their alignment and one contains a mattress that fills the sill for a bed. The hide has a roof light - like many of the projects. The smaller the space, the more important good natural lighting is to reduce a feeling of claustrophobia.

One design, Hundra Kubik by Arkitektstudio Widjedal Racki is shown being transported to its site on the back of a low loader. It is one of the most elegant designs and provides accommodation for four with sleeping platforms within a low mezzanine. It has several clever ideas to expand the space so one end hinges out to enclose in part a terrace to make an outside room to expand the living accommodation and at the other end the end wall itself and short lengths of the front and back wall with it slide out like a drawer to form an enclosed area but without a ceiling for an outdoor shower.

With pressure on land in even well-established cities, the ideas here for building kitchens in the smallest possible area or fitting in toilets and showers in little more than a cupboard are a real lesson in compact living. Maybe too compact - as one scheme by Belatchen Arkitekter called 20/25 has bedrooms or ‘private’ spaces for twenty students housed in a series of squat cubicles like drawers on either side of a narrow corridor that includes a kitchen and bathroom.

Ateljé 25 from Waldemarson Berglund Arkitekter has a pitched roof with a full-height window/door with a roof light up the slope of the roof in line to create as much light as possible without loosing too much wall - crucial for fittings in such a small space. Several alternative plans were shown with either just a kitchen and living area or in others with a bed and a bathroom included so this seemed to be a design for a very elegant holiday lodge.

One design is for a complete folly - Triumfbågen by Tham + Videgård - a triumphal arch in front of what is itself a relatively small house. The archway has arched openings on all four sides so relatively narrow piers at each corner … one containing a toilet, one with a store for garden tools, one for a store for bottles of wine and the fourth with a tight winding stair up to the flat roof which is clearly a viewing platform or a deck for sunbathing and the point of the building. It has over the entrance arch the inscription VENI VEDI VICI.

The architects who participated include:

Earth's architects, Bornstein Lycke Fors, Dinelljohansson, Vision Division, Kolman Boye Architects, Happy Space, Wingårdhs architectural office, Nordmark & ordmark architects, Belatchew Architects, Jägnefält Milton, Marge Architects, Architect Studio Widjedal Racki, Okidoki! Architects, The Commonwealth Office, Johannes Norlander Architecture, Marx Architecture, White Architects, Elding Oscarson, Waldemarson Berglund Architects, In Praise of Shadows, Testbedstudio, Petra Gipp Architecture, A blast, Trigueiros Architecture, Tham & Videgård Architects.

A book of the designs, 25 Kvadrat by Eva Wrede and Mark Isitt was published by Max Ström in November 2014.

The exhibition continues at Form Design Center in Malmö until 7 June

A new exhibition, Ung Svensk Form, opened at the Form Design Centre in Malmö on Friday. It is a show by young Swedish designers and includes textiles, ceramics and glass, furniture, jewellery and fashion.

This is a competition and exhibition that has been staged ten times by Svensk Form since 1998 and many previous exhibitors are now well established either within the Swedish design professions or internationally. It is open to students and to young designers under 36. As well as the exhibition of their works which go on tour, designers are awarded scholarships, practical placements and workshops to gain more experience and an understanding of production processes.

The works included prototypes and concepts to show artistic experimentation.

A list of the designers and a copy of the exhibition catalogue are available on line.

The competition and exhibition are supported by IKEA and the Stockholm Furniture & Light Fair.

The exhibition continues at Form/Design Center in Malmö until 7 June

Superobjekt Gallery from Borgergade

Vibeke Rohland talking to a visiting art group on the day after the opening

An exhibition has opened at the Superobjekt gallery in Borgergade in Copenhagen showing recent works by the artist and designer Vibeke Rohland.

Normally, I do not post about artists or about art gallery exhibitions on this site - trying to keep up with design and architecture is enough of a struggle for me without getting distracted, however pleasant or interesting that would be - but the meeting point of art, design and craftsmanship is incredibly important. And that is exactly what you can see in the Crossroads exhibition.

Marketing men and accountants, I am sure, see the different ‘disciplines’ in different boxes but one of the huge strengths for Nordic design in general and for Danish design in particular, is that the separation of roles in academic training and in professional practice is blurred. In Denmark many furniture designers have trained initially as architects, product designers come through a craft background as makers, designers appreciate that they have to understand the craft techniques as the starting point for commercial production and, through a long well-established tradition, many classic pieces of furniture have been produced by a close collaboration between the designer and cabinet makers.

However, even in my own mind, it is difficult to define clear boundaries. At one end of the scale a unique piece, signed and often dated because it can be seen as part of a sequence in the development of an artist’s work over the years, is clearly ART and at the other end of the scale something produced in a distant factory and shipped back for sale is product design. Between though is the problem. A potter or glass maker might make a one-off piece for an exhibition; a set of matching pieces - a series of handmade pieces - for a client and then a related design for mass production by a well-known design brand. So one unique piece is a work of art, a set is crafts-made, and more than ten? more than twenty? several hundred? several thousand? becomes a product run? And how should artists, makers and designers interact? Surely they have to! Surely a designer needs to check back in to making something by hand every now and then and a craftsman could benefit from the occasional fee of a commercial run.

Vibeke Rohland very clearly and deliberately breaks through these boundaries. Here, at the Superobjekt gallery, many of the large and unique pieces are actually produced over commercial fabrics that Vibeke designed and that are made by Kvadrat. Even the techniques shown here are a beautiful subversion. Many of her pieces with a limited-run as well as the commercial designs have been produced by silk screen printing so always with slight variations because it is not, strictly, a mechanical process.* Here, for the largest pieces in this show, the dye has been laid on and taken across the fabric using a squeegee but without the screen and its mask as the control or intermediary. Each area of colour therefore is and has to be a unique area of the overall work. There can, obviously, be no precise repeat pattern. The colour appears to be built up in layers and that is exactly what has happened.

A recurrent theme of Vibeke’s work is using what appear to be simple repeats of pattern but with complex overlays of colour using intensity of colour to create changes in the depth, light and space within the pattern. A series of grid or cross-hatched designs, some framed and included here, and experiments she has produced with large wheels or circles as the underlying form, created with broad cross spokes, uses the same approach ... being apparently very bold but actually creating a finished piece that is incredibly subtle in it’s use of colour and it is the variations in the intensity of colour or variation in the thickness of pigment which create the sense of depth. Another series uses strict repeats of large but simple shapes like crosses or dashes but on a huge scale to undermine the viewers judgement of distance from the work. The repeat becomes a texture but again not something mechanical because it is slight but deliberate changes or slight differences in the units over a surprisingly large repeat making up the pattern that bring the design to life.

Again, this same approach to colour and pattern can be seen in the commercial designs by Vibeke for Kvadrat. Her commercial woven and printed textiles use small points or fine lines of colour to build up pattern and form and shadow so it actually comes as a surprise when you see the large overall size of the repeat of the pattern. In the same way that the layers of colour on the pieces in this show build up to form a complex and large-scale work, the small points of colour and the very very careful combinations of colour in the furnishing fabrics are used to create depth and an effect of shadow to build up the final bold overall pattern.

The works on show here are amazing but it is also worth tracking down the commercial designs from Vibeke Rohland that have been produced by Georg Jensen Damask, Bodum, Hay and Royal Copenhagen. Spend time looking at the on-line site from Kvadrat to see the designs for fabric there - including Map, Satellite, Scott and Squares - with a wide range of colours in each design. The small sample at the start of the Kvadrat page reduces these textiles to a simple small area of dots or graph-paper grids but clicking through and moving out to the broader view these become complex patterns that are again both bold and subtle ... that same effect as you move close up to and then further back from the pieces in the gallery.

CrossRoads continues at Superobjekt Gallery Borgergade 15, København until 2 May 2015

There is just a week left to see the exhibition at the Danish Architecture Centre about climate change that shows how urban planning and the design of buildings and hard landscaping have to adapt now for changes in weather patterns in the future.

Looking up from my desk, as I’m writing this morning, it is raining but it’s really the sort of shower that anyone would expect at this time of year … late March so Spring in north-west Europe. This is not the sort of weather the exhibition is talking about but then back last summer, just a couple of weeks after I moved into this apartment, Copenhagen had one of the flash rain storms that are becoming more frequent here. There was torrential rain for several hours and the street drains could no longer cope and pools of water started to form across the road and pavements. Like many apartment buildings in the city, we have a basement where residents store boxes and bikes and so on. I had a phone call to say the basement was flooding, because the pump had failed, and was told that if I wanted to save or salvage my things down there I should do it right away. It was hardly a disaster for me - I lost a couple of cardboard boxes - but further along the street several businesses in semi basements, four or five steps down from the pavement, had much more serious problems. Industrial pumps were called in but most of those businesses had to shut for several months as floors and electrical systems were dried out or replaced. Six months on and at least one business has still not reopened.

For a city like Copenhagen, new developments with ever denser building with more and more ground covered with tarmac or hard surfaces, designed to drain quickly, it actually means there could be dramatic consequences if these sudden rain storms become more frequent as predicted.

And these storms are dramatic. On the 2nd July 2011 there was a rain storm in Copenhagen where a fifth of the normal annual rainfall fell in just three hours. Neighbours have told me that whereas this time I had to move my things out of less than 10cm of water, on that day the basement rooms filled right up to the ceiling. In the city underpasses and road tunnels were flooded and closed, utility services were lost and the extent of property damage was phenomenal.

Having said all that, the exhibition is not all about doom and gloom. In fact far from it as the real message is that we have to accept that these changes are coming and therefore we should start to adapt our construction methods and planning to make appropriate changes now. Simply planning for an emergency response, for if and when, is not a sensible approach. By starting now we can be in control and there will be gains because making changes in advance “presents us with a unique opportunity to improve our cities and create greener cities with more open spaces where rainwater can be handled and urban life can thrive.”

The first part of the exhibition shows with excellent graphics how much more of the city is now built over so the natural process of water soaking into the soil or running away along natural drainage channels is no longer possible. In the past rain water and dirty waste water … so everything from water on the roads contaminated with oil from traffic to sewage has been dealt with through the same system of drains or, where there are separate storm drains and household drains, these often back up and contaminate each other when the system is under pressure when there is a sudden storm.

There is also a stark lesson to be learnt from the past about what happens when you prevaricate. By the 19th century Copenhagen was densely built up with houses and businesses tightly packed around narrow streets and courtyards. Then the problem was not surface drainage but dealing with human waste. There was no sewage system in the city and in 1835 a cholera outbreak killed thousands of people and started a discussion about the need for drains. Political differences, problems with financing such extensive work and potential disputes dealing with individual land ownership stymied any progress until the 1850s when a second major outbreak of cholera killed 5,000 people in the city. Even though work then started on clearing slums and improving the drains it was not until the 1880s that Charles Ambt, the city engineer, began to draw up detailed plans for the necessary engineering works including a scheme to take sewage out through a tunnel under the harbour and out into the sound. The Nordic Exhibition in Copenhagen of 1888 showed the citizens all the wonders that were then available for modern plumbing and sanitation but even then the first street to have water closets was Stokholmsgade in 1893, nearly 60 years after that first cholera outbreak, and it was not until 1901 that Copenhagen completed a full sewage system and paved the streets in the city. To be blunt, the point here is that this time, facing climate change, we cannot afford to take sixty years to decide what to do and start the work.

The second part of the exhibition shows a number of completed or ongoing or planned projects that are designed to cope with the anticipated increase in the number of rain storms. These are presented as opportunities rather than enforced and expensive solutions that will be necessary if we wait until we have to do the work.

With adventurous and imaginative schemes the people who live in the cities and in the suburbs are getting new facilities and renewed urban areas at little or certainly reduced direct cost; the city councils are getting a renewed infrastructure at markedly less cost than by waiting until works are absolutely needed after a major and destructive storm and the utility companies, who have to provide solutions and have to deal with any failures in the system, can actually often introduce smaller local schemes on private or city land as long as the owners see a gain which is much much cheaper than the company having to buy land for the construction of mega solutions.

Simple schemes shown include designs for permeable pavements and surfacing to deal quickly with surface water but without overwhelming the drains. On a larger scale there are several proposals shown to build underground tanks to hold water from flash floods so it can be dealt with slowly over the following days and weeks. More natural-looking options - rather than hard engineering solutions - include schemes with planting or new ponds and drainage channels or well-planted temporary flood plains. New artificial surfaces can be installed for sports facilities that keep the surface dry but take rain water down to permeable sub structures.

So, at Gladsaxe new sports facilities for the Gymnasium have been built around and over ponds and canals for a new drainage system that holds back flood water so it can be dealt with locally by the system over a more reasonable period. For this project costings have been given to show how the different parties have benefitted financially. A traditional project with an underground storm basin would have cost 102 million DKK. The completed project with surface solutions cost 72 million DKK. The municipality has influenced the project and gained financially by providing advice and expertise that was financed from the project costs. The citizens of Gladsaxe saved 30 million DKK on supply expenses and they gained sports facilities, playgrounds, nature trails and new urban spaces.

At the headquarters of Nordisk a nature park of 31,000 square metres has been built with half laid out across the roof of car parks. Covered with grass and meadow plants, it absorbs rain water rather than having it run off the alternative of hard roofing into drains and provides a pleasant new facility for staff and visitors to the company.

In Middlefart management of water is seen as an opportunity to create a Climate City to turn 450,000 square metres into a greener and healthier neighbourhood.

In Køge there is scheme to establish new green spaces and rain water from roofs will be cleaned and returned for washing clothes and flushing toilets.

In Viborg a large new park is being laid out with lakes that retain water that can be cleaned and returned to the water system. Again there is considerable gain from such careful management of storm water … the utility company gains access to a large space where it can manage and clean the water, the municipality can influence the design from the start and gets a new park and the citizens are protected from flooding caused by a sudden cloud burst and gain a new recreational space.

Not all the schemes are on such a large scale. Helenevej in Frederiksberg is the first climate street in Denmark with a permeable surface that absorbs large amounts of water when there is a cloudburst and at Vilhem Thomsens Allé in Valby, rainwater is handled within the courtyard of the housing scheme creating a recreational space and reducing water bills as retained water is now used rather than metered water for watering the planting. The utility company gains financially because it does not have to construct new pipes to take rainwater away from the area.

If people still need to be convinced about the need for such schemes, the exhibition has stark figures for the financial cost of wasting water. An average Danish family uses 40 litres of water per person each day for flushing toilets and for washing which is roughly the amount of rainwater that could be collected from a roof surface of 40 square metres so if water could be stored until it is needed then the roof on a house, on average 200 square metres, could provide all the water needed for washing clothes and flushing toilets rather than the family using drinking water … with a potential saving for a family of 5,000 DKK a year in water charges.

The Rain is Coming - how climate adaptation can create better cities

Danish Architecture Centre until 6th April 2015

type a keyword in search for a list to drop down

type in keyword plus return for all entries to be displayed on a separate page

longer posts are under main subjects - the headings to the right are links to take you to the long posts on that subject

or for related posts go to a category - shown under each post - and set out below

posts are also linked by tags

architecture, planning and design in context along with thoughts on craftsmanship and manufacturing and ideas about style

news and notes with photographs and thoughts about design,

architecture, planning, townscape and exhibitions in Copenhagen

Powered by Squarespace