balcony blight has spread to Jægersborggade *

/With Coronavirus lockdown restrictions, it has been many months since I have been up to Jægersborggade but Saturday was sunny, and I needed some exercise, so I walked up to the lakes and then on along Nørrebrogade and through Assistens Kirkegård.

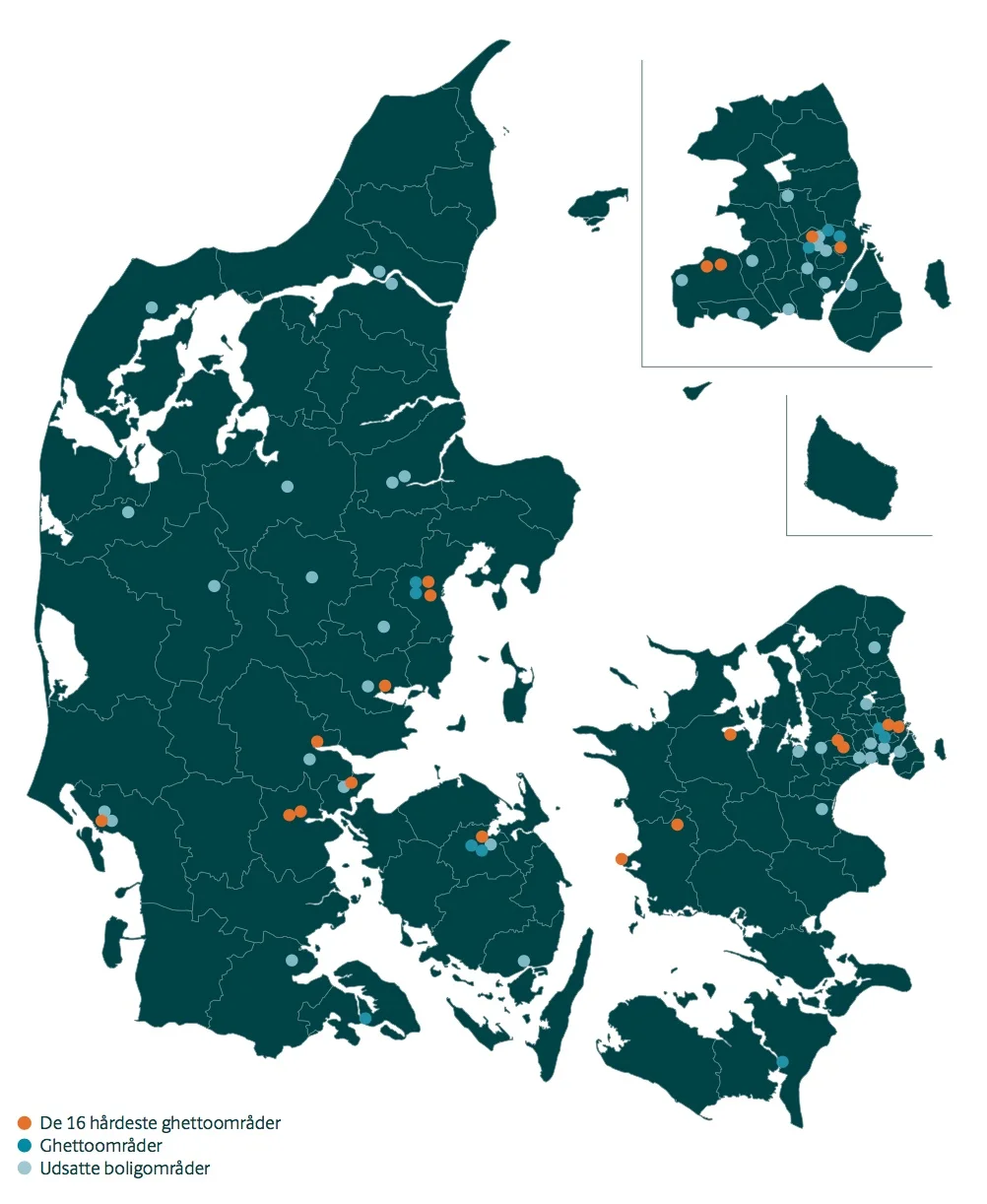

As soon as I got into Jægersborggade, opposite the north gate of the cemetery, I could see that construction work had started to add balconies to the front of several of the west-facing buildings.

This whole business of retrofitting older apartment buildings with new balconies has become a serious problem in the city.

Copenhagen has a phenomenal number of good apartment blocks that date from the 19th and the early 20th century ... apartments that were built on new squares and new streets as the city expanded rapidly with large new districts built over the fields and gardens beyond the old city gates.

Most of these apartments still form an important part of the housing stock in Copenhagen and most, even if the original arrangement of rooms was restricted or not completely appropriate for the way we live now, they can be easily adapted .... so heating and bathrooms and so on can all be upgraded. Even replacement doors and windows that comply with modern building standards for sound and heat insulation can be found in an appropriate style and colour that either replicate or compliment the original fittings.

But few of these buildings had balconies.

Of course, I can see why people want a balcony and particularly a balcony that faces the sun or looks across an attractive street or square. A balcony can bring extra light into a room; can be a space to grow herbs or plants; and, if large enough, can be a place to sit and sunbathe or even provide space outside to have a table and chairs for a meal.

Balconies are fine when they form part of the original design and are part of the original construction on apartment buildings from the 1930s or on modern buildings but inserted on the street frontage, they inevitably slam through the original architectural features of the facade, compromise any architectural style the building may have; add what are often little more than stark metal boxes across the front and usually throw shadow across the windows of the apartment below.

With many of these older apartment buildings, the street frontage and a main staircase, are the only parts with any architectural coherence. In most, the back of the building is far less distinguished or, worse, a muddle of toilets and back or kitchen staircases but rooms on the back of the apartment can look down into gardens or attractive courtyards so balconies added to the rear of building are rarely an issue.

* blight covers green leaves on a plant or tree with ugly and disfiguring areas

shopping in Jægersborggade - December 2018

Jægersborggade - May 2021

retrofitting balconies is a problem - January 2020