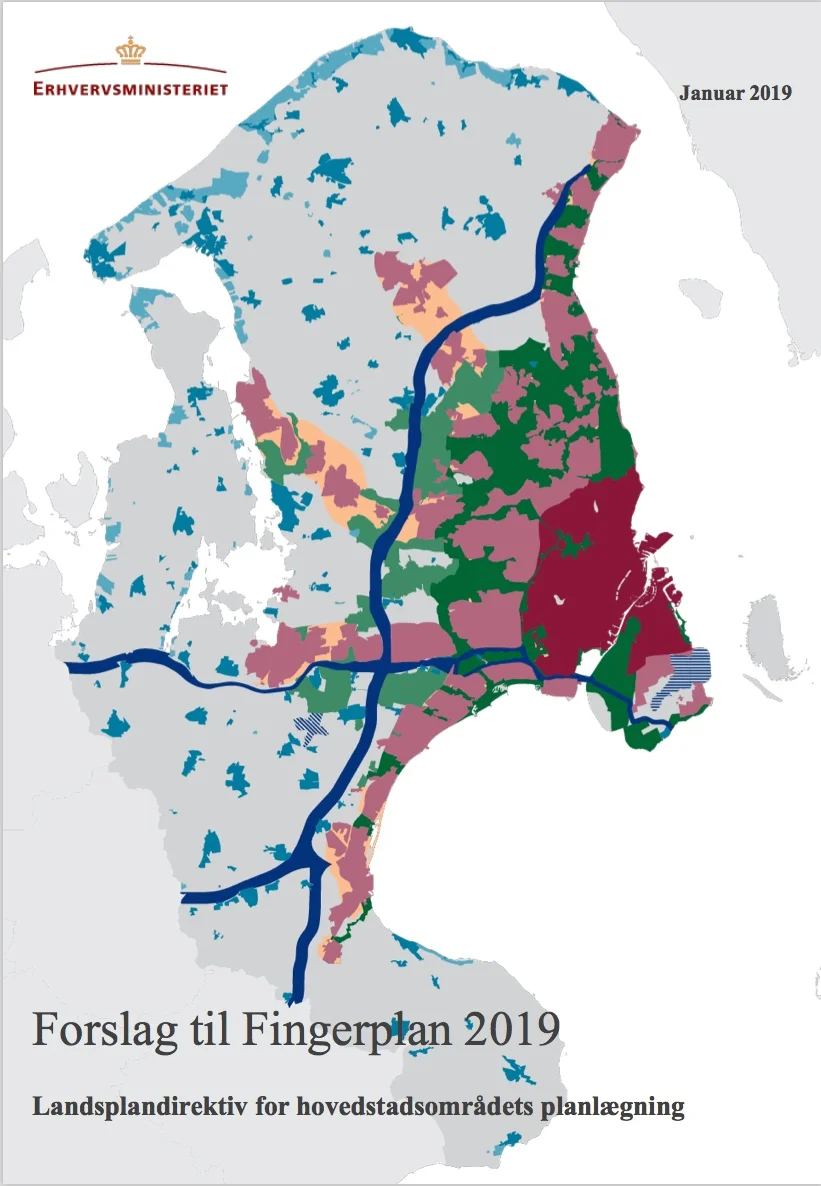

Forslag til Fingerplan 2019 - Landsplandirektiv for hovedstadsområdets planlægning

/Suggestion for Finger Plan 2019 - National land directive for the planning of the metropolitan area

the new Finger Plan has a series of maps to illustrate changes to planning in the area around the historic city of Copenhagen

A major revision of the famous Finger Plan of 1947 was initiated in April 2016 and after a period of public consultation - when the 34 municipalities of the capital region were given time to submit comments - a first version of a new plan came into force in June 2017,

Published on 24 January 2019, this is the next stage of that report and there will now be a period for public consultation through to 21 March 2019.

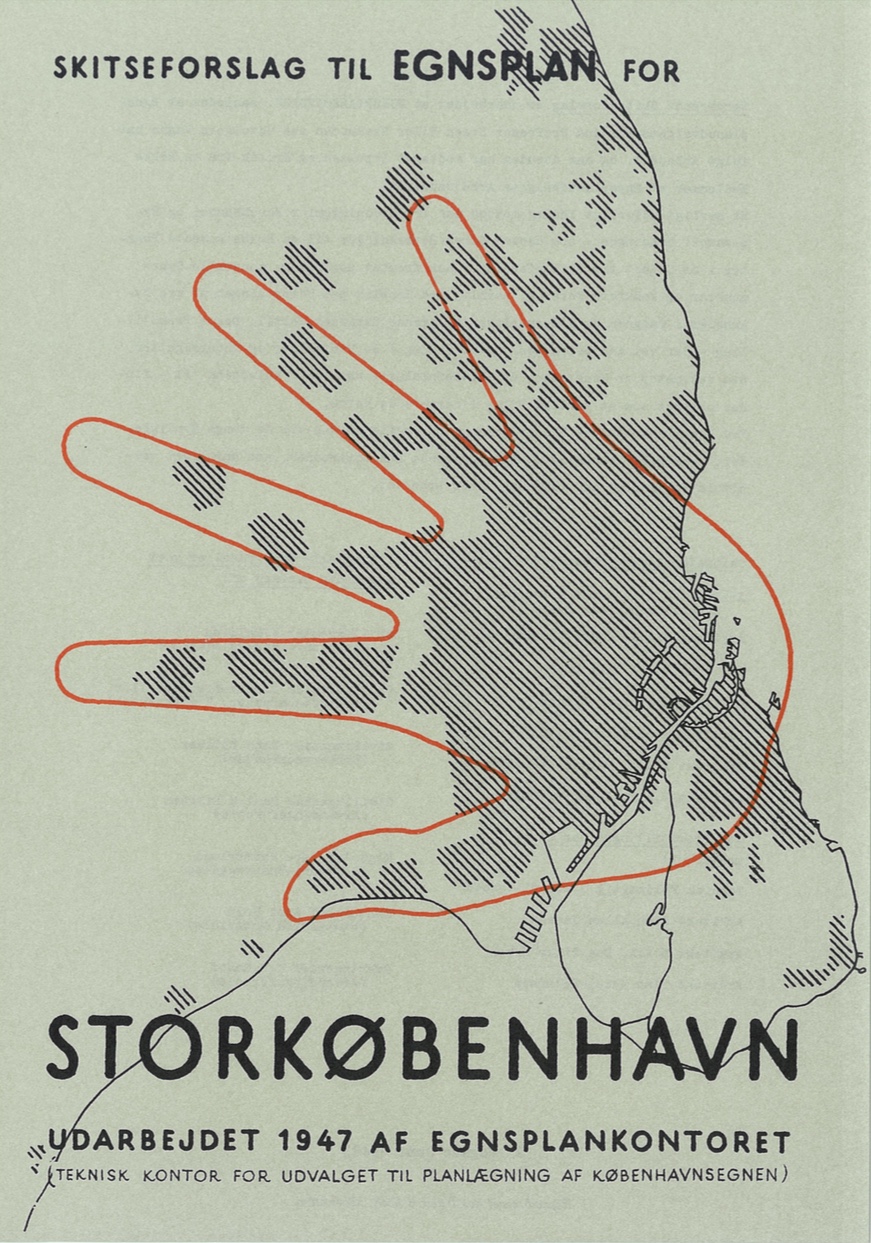

The Finger Plan from 1947 was a key planning report that set the course and controlled the form and the extent of development out from the city through the second half of the 20th century and its influence has continued into this century so it has had a huge impact on the city for more than 70 years.

That plan, to control development, was based primarily on existing lines of the suburban railway that radiate out from the centre of the historic city and new development has been centred on railway stations but with a web of green open space between the fingers … protected countryside that has been crucial as space for nature and for recreation that has stopped the expansion of the city from becoming a solid urban block like London or becoming a sprawl of unregulated development.

The new plan is setting out how to allow for but control further expansion of the city and the region through to 2030 and beyond and it will focus on problems caused by climate change that makes green space and the control of surface water and flooding from the sea increasingly more important. Protection of green land is seen now to be a balancing act and new proposals will be controversial as some green areas could be lost - for instance where they are compromised by being close to major transport links - but there appears to be a commitment to add new areas of protected green space and particularly where this has a clear role in enhancing recreational use.

In 1947, the original Finger Plan, set out the principle that development should be along the suburban rail lines with large buildings, such as city halls and shopping centres, close to the railway stations but the new plan will give the municipalities more freedom to plan for larger commercial buildings with some users up to 1000 meters from the stations in the towns of Helsingør, Hillerød, Frederikssund, Roskilde, Køge and Høje-Taastrup.

Three special areas are designated in Nærum, Kvistgård and Vallensbæk, where it will be possible to plan for larger commercial buildings with many users.

Planners and politicians want to strengthen secondary retail development in the metropolitan area with enhanced areas for local retail in Hillerød, Ishøj, Lyngby and Ballerup along with development in Helsingør and a new town center in Kokkedal.

The report includes proposals for major developments on new land that will be claimed from the sea with Lynette Holmen, a new artificial or man-made island across the entrance to the harbour - where there will be housing for 35,000 but also the island will be part of major coastal defences to protect the inner city from flooding if there are storm surges in the sound. South of the city, Avedøre Holme will be a group of new islands that, primarily, will be for major industrial development. It has been suggested that these developments will bring 42,000 new jobs to the city.

Under consideration is a section of new motorway around the city with the construction of what is called Ring 5 north from Køge, to follow a route between Copenhagen and Roskilde. Presumably, this is connected to assumptions that new traffic will be generated when the road and rail tunnel between Germany and Denmark is built. That international link was given final approval by the German region in December and could be open by 2035. An outer motorway west of the centre would be important for the region because it is possible that by the middle of the century a new major engineering project could be justified so building a bridge or tunnel link between Helsingør and Helsinborg in Sweden that would create a Hamburg-Copenhagen-Stockholm axis with the German and Swedish cities just 500 miles or 800 kilometres apart and with Copenhagen and Malmö at the centre point.

The text of the new plan is set out as major bullet points simply because this is a document for the next stage of consultation but, even at this stage, it is worth reading because local citizens should see this as one way, at the very least, of understanding how their city could develop over the next decade and, of course, like the original Finger Plan, it will set the framework for life in the city and for the built environment of the city through to the middle of the century and probably for a much longer time frame. What the report does have, even in this version, is attractive and informative graphics with a series of maps that make the hard data and the stark proposals easier to see in terms of specific areas and their potential extent and their impact on the landscape.