a Belgian viewpoint

/

At northmodern this year there were seven designers from Brussels chosen by the architect and designer Julien de Smedt who also designed the exhibition stand that was set in one of the large central halls.

The exhibition was promoted and co-ordinated through MAD Brussels - the Brussels Fashion and Design Centre - and Brussels Invest & Export.

Included were textiles from Sarah Kalman and the design studio nomore twist, furniture by Alain Berteau and by Alain Gilles, lighting by the designer Pierre Coddens, work by Pierre-Emmanuel Vandeputte (who also showed his work at northmodern last August) and work by Jonas Van Put.

What seemed to distinguish three of the designers, in slightly different ways, was that their work was ideas led rather than initiated by a product brief. The reality of much design work is that a manufacturer or design company will approach an independent designer with a commission that has a fairly tight brief that essentially and inevitably means starting with preconceptions about the starting point and the end result.

What should be more interesting but is possibly more of a risk (in terms of commercial returns) is to give a designer the time and space to approach the problem from a different direction or to consider a completely unconventional material or to simply think about and design something where the need or the use has not been identified.

Jonas Van Put

An interior architect and designer, Jonas Van Put actually doesn’t just want to have a different starting point himself but wants the user to have a different view point.

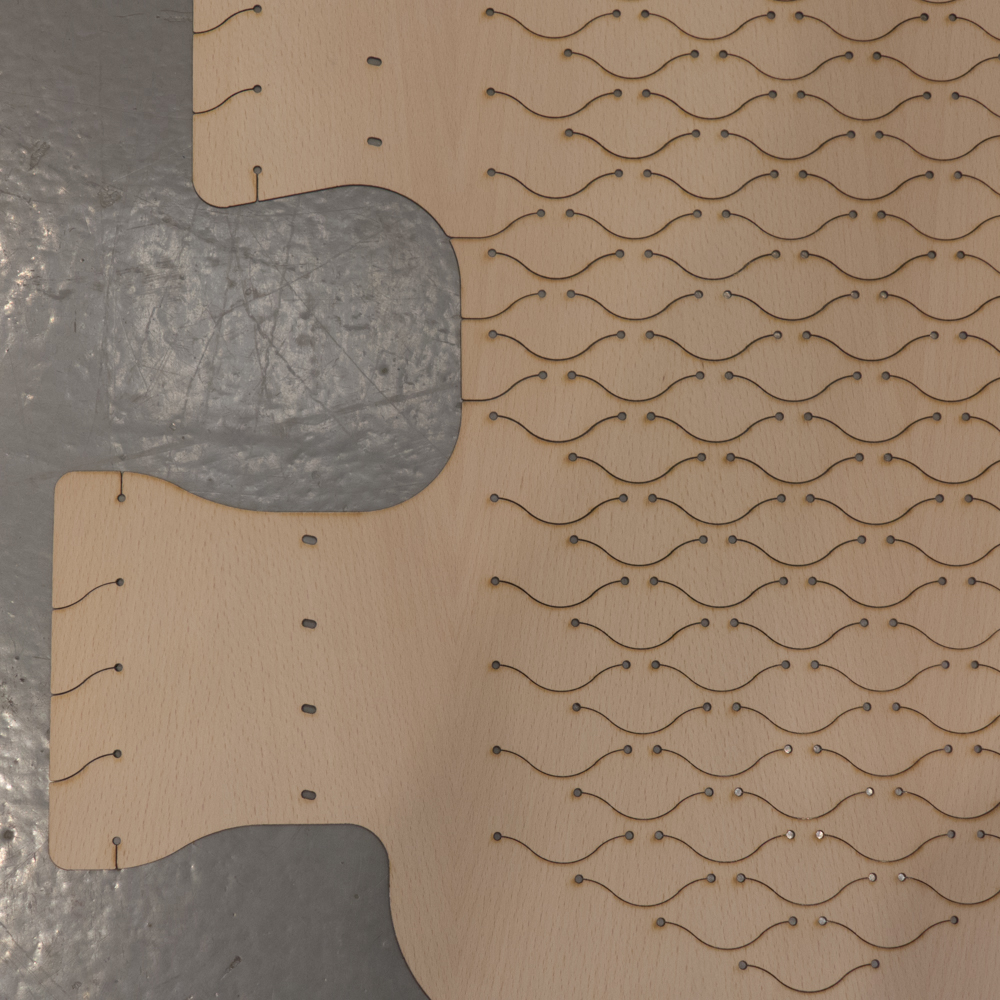

Observer was designed when Fritz Hansen provided a number of chairs in the Series 7 to the design school to encourage students to adapt and reinterpret the famous design by Arne Jacobsen to mark its anniversary. Jonas constructed a slim pyramid-shaped metal tower not to alter how we look at the chair but to alter what we see from the chair.

The catalogue to the Belgian section includes the fascinating information that by raising the chair up to take the eye level to 5.2 metres the distance you can see from the chair nearly doubles to 8 kilometres.

Pangea is described as a conversation piece with woven platforms or loungers at various levels on the steel frame. Jonas described how he had been inspired by looking at a jungle canopy and that the space between levels gets closer and more constricted at the lower levels. It was interesting to see who climbed up and how far up they went and as the loungers are set facing in different directions not only height but the view point changes as you work your way up the tower.

Both pieces and the works by Pierre-Emmanuel Vandeputte are one off and hand made. Talking to both designers it was clear that finding workshop space and materials was often a matter of trading off skills on a sort of designers barter system but this was seen by both as a very positive way to learn new manufacturing techniques and skills first hand and as an opportunity for exchanging ideas with other artists or skilled mechanics or craftsmen. Exploring and learning and adapting and manipulating ideas and materials was an essential part of the design process.

Pierre-Emmanuel Vandeputte

Pierre-Emmanuel Vandeputte graduated from La Cambre in 2014 and showed some of his work at northmodern in August 2014 including the Cork Helmet … a way for the user to cut out from the noise and distractions around … and Belvedre … again a raised seat to encourage to user to take a different view point on the World.

Ecco Freddo, shown this year, is a modular system in fired clay that addresses the problem of how we store and keep food … here using sand for root vegetables and double layers using the condensation of water to keep food cool and fresh without resorting to refrigeration.

This approach … taking a step back and looking again at how we do day-to-day housekeeping tasks is reminiscent of the approach by the product design students from Lund who showed their project work at Form in Malmö last year in the exhibition The Tomorrow Collective.

It was interesting to listen to Pierre-Emmanuel describe how he worked with a potter to produce these pieces, adapting the design as he learnt more about the material and the techniques required … much like his approach to understanding how watching and learning from the methods of the glass blower meant he modified the design of his Wine Carafe.

Alain Gilles

Alain Gilles is an older and slightly more established designer although design is actually his second career as he changed to industrial design after studying Political Science and Marketing Management and after five years in banking.

At northmodern he exhibited three pieces … Grove, a group of low round tables, The Pure, a football table, and his leather and steel sofa called X-Ray. Visually, the three pieces are different in style but linked because they are all very much about how the user reacts with the piece.

The set of tables in different heights and with different finishes on the top are about how they are set in relation to each other. The football table is tactile and very much an adult play thing rather than a child’s toy. Brushed steel handles on the rods, the figures of the players, like steel skittles but with a look of spacemen, and the integral score boards set into each end are carefully refined.

It was the sofa that was really intriguing. It’s a good few steps away from traditional upholstery and seems to approach the design problems from an engineering perspective … what might be produced by an engineer if commissioned to design a sofa.

The elements have been stripped back with a simple, exposed metal frame, a wooden top rail across the back, like a handrail on a staircase, to support the back cushions but swept round at each end to form arm rests and simple straight-sided leather cushions for the seat and back with smaller cushions at each end. Its success as a design is in the way it disguises just how much care has gone into the design of each of these parts so, for instance, the side cushions are upholstered around metal armatures that dropped down into slots in the base cushions so the leather had to be perfectly cut and sewn around these slots - an expensive and clever but hidden detail.

Alain tried to convince me that the sofa is really comfortable by sliding down into the sort of slumped recline that most men adopt on most sofas to watch TV. But my problem with low upholstered chairs is that because I’m tall then seating designed for average-height people - particularly low upholstered seating like armchairs and sofas - makes my neck and back ache very quickly so I pushed the base of my spine right back into the seat and sat bolt upright. Alain presumably thought I was just being an uptight Englishman but actually I was testing the comfort and found that the carefully constructed and firm upholstery and the angles determined by the frame of the back and the frame under the seat cushions provide really comfortable support. Some designers and manufacturers seem to think that soft equals comfortable whereas in fact comfort comes from well-designed support … in the case of the back and neck, supporting the lower back well is actually what allows the upper body and neck to relax.

The sofa illustrates well another aspect of good design because, as so often, the Devil is in the detail and it’s a matter of knowing where a very carefully thought-out detail contributes to the whole - so here the rounded end of the legs rather than having them cut sharply square - repeats the termination of the wood back rail - and pulling the ends of the lower frame outwards to sit under the curve of the back rail creates the sense of the framework of a box containing the cushions.

Red and dark blue used for the metal reinforce this idea of an outer box scaffold by consciously or sub-consciously picking up the way the artist Mondrian broke down and simplified his images to a strong frame and simple blocks.