update on the Y Block in Oslo by Erling Viksjø

/Approaching the site from the south

It looks as if the Norwegian government is moving slowly towards a decision to demolish the Y Block in central Oslo, one of the major government buildings that was damaged in the bomb attack of 2011, but retain the tall but separate H Block to its east. Both buildings were designed by Erling Viksjø - the Y Block was completed about 1970 while the Høyblokken or H Block dates from 1958.

Articles today on the web have focused on the murals designed by Picasso that decorate the large concrete panel on the south end of the Y Block and staircases inside the block with some suggestions that these could be salvaged and reused.

What should also be discussed is the quality of the design of the buildings and the positive contribution that the two blocks make to the townscape of this part of central Oslo.

When I walked around the buildings a year or so ago (see the post written then) there was no access to the interior but although windows had been shattered and were boarded up there seemed to be no sign of major structural damage … pedestrians were able to walk up to the building and the main road tunnel immediately under the north end of the building was still open for its heavy traffic use so there was obviously no worry about imminent collapse. In fact, in late September the public was allowed into the building to look at the interior.

The Y Block from the north west

Judging from photographs, the interior of the Y Block is not extravagant or ambitious in terms of its decoration and planning - simply practical and sensible - but it does appear to be well proportioned, the rooms light and main features such as staircases actually quite elegant.

What struck me, walking around the exterior, was that photographs really do not do the Y Block justice. This is not some brutal concrete structure that only an architecture fanatic could admire. The scale is very good, the proportions elegant and the arrangement of narrow windows on the three upper levels, divided by thin fins of concrete, is a welcome relief from the unbroken horizontal runs of tinted glass that has been so much in favour for commercial office buildings over the last 30 years.

Air view of the site with the Y Block at the centre and the H Block immediately below to the south. The curve of Akersgata running approximately north to south is along the left (west) side of the photograph. Taken from Google Maps.

Plan taken from OsLocus by Sofie Flakk Slinning

Much more important is the skill with which these two buildings, the Y Block and the H Block, sit in the landscape of this area. The ariel view shows how the Y shape, with its elegant inward-curving sides, is not a conceit or a whim but is very carefully considered so that the building works well within a complex site. Particularly on the west side, approaching along Akersgata from the south, from the centre of the city, the opening up of the square - Johan Nygaardsvolds Plass - the angle of the front set back but showing clearly the main points of entry and the facades curving away, indicating the overall scale of the building, all make perfect sense visually. With the curve of Akersgata the approach from the north also reads well as you come down the road towards the centre and the open public spaces on the north side and the precise, careful positioning of the north range of the Y Block show a huge respect for the three historic buildings along the north boundary.

The large building across the south side, Block G of the Ministry of Finance completed in 1906, is itself severe but the more formal relationship it has with the H Block set at right angles again provides appropriately dignified accommodation for the major government departments that were here and included the offices of the Prime Minister, the Justice Minister and the Education Ministry.

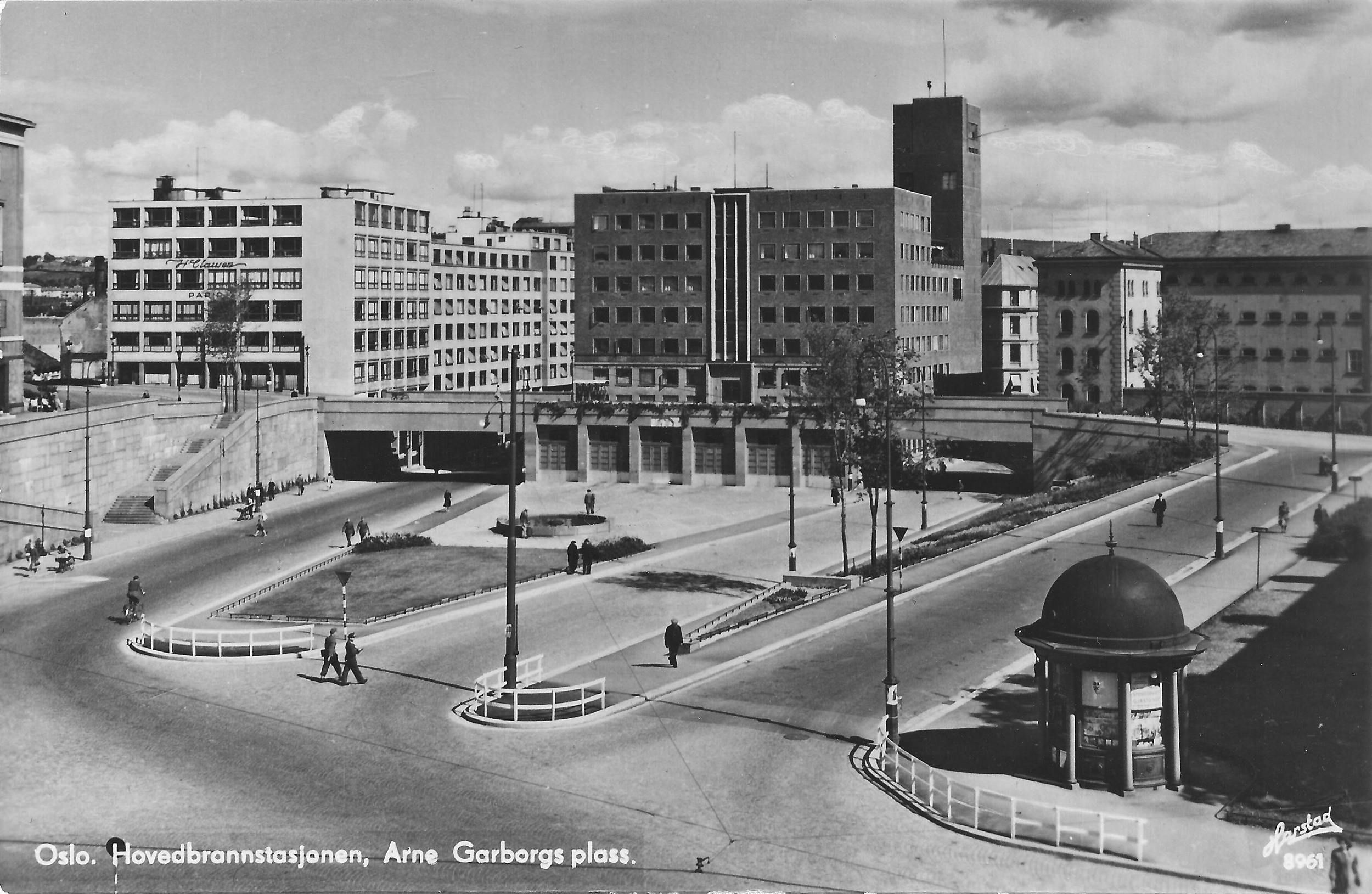

The tunnel of the busy dual carriageway under the north side of the site is actually at the natural ground level of a broad valley so the open paved areas were created on what is essentially a raft raised over the former Arne Garborgs Plass. This creates a series of pathways and steps and with the circular and curved light-wells forms an interesting, well-executed and quite dramatic pedestrian landscape.

It is actually the more recent and much more grim buildings along the east side of the site, on the east side of Grubbesgata, S-Block and Block R4, that need to be rebuilt or remodelled and the very very poor quality of the street surface, paving and street furniture along Grubbesgata do much to undermine and diminish the quality of the architecture by Viskjø.

From the north above and approaching the site from the east along the underpass

It would be difficult to justify the demolition of the Y Block if it is simply because this large central site could be better used with more densely packed and taller buildings or because it is no longer suitable for the government departments that were in the building because they have now become well-settled in new accommodation elsewhere in the city that they were moved to after the bomb attack.

This post was altered on the 6 December to incorporate a number of additional photographs and a plan taken from the Wordpress site, OsLocus, by Sofie Flakk Sinning that was part of a project on Architecture and Politics completed in July 2012. I strongly recommend looking at that site for an extensive analysis that makes many interesting and important points about the symbolism of the architecture of power and politics and the very real problems now with necessary security measures.