brick cladding

/Out near the beach on the east side of Amager there are large new apartment buildings that are going up and at an incredible speed because of the method of construction being used with large panels of preformed concrete lifted into place by huge cranes before then being fixed or linked together.

Then, on the outer face, goes insulation and a veneer of brick in large sheets made in a factory …. and that is where I begin to have reservations.

There is nothing wrong with the building method - and the advantage is that very speed of building - but then my inner puritan kicks in. I notice the long straight joins between the panels and think that this really has little to do with real brickwork … basically because brickwork isn’t, curiously, just about bricks but also about the mortar and the courses and the patterns - created by how the bricks are laid - and how different colours of brick and how different colours of mortar effect the appearance.

Then there is the thing about honesty … that’s not honesty as in money and value but honesty in design so about using building materials in an appropriate way that reflects and uses the intrinsic qualities of those material. Here I can see that brick facing is used for these modern apartment buildings because people like it - it’s somehow more reassuring and warmer and more comforting than concrete or glass - and because it can be a good attractive colour and, at least, brick does provide an element of texture that can be missing from many cladding materials.

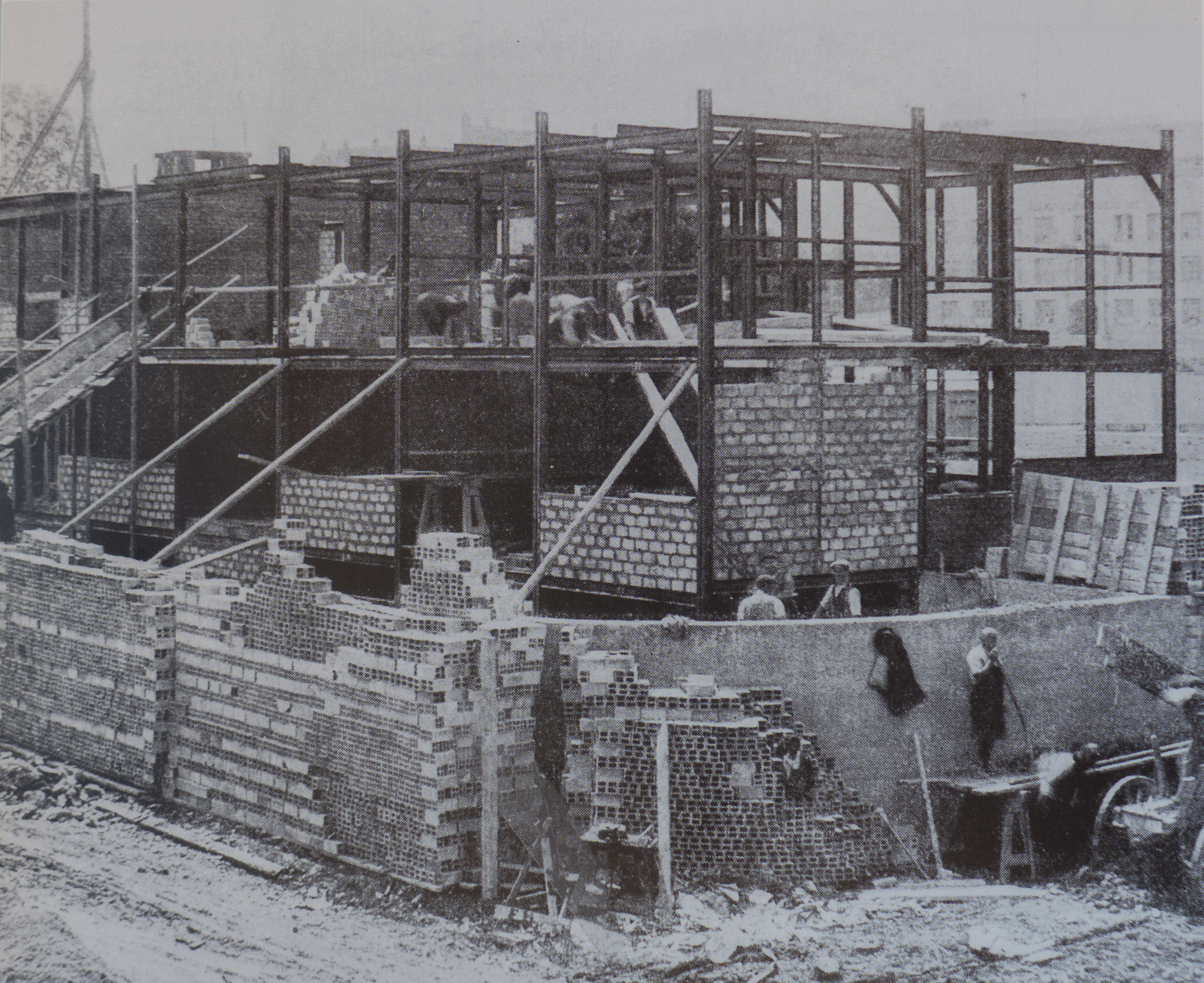

Which is sort of part of the irony here … it is a factory made product - manufactured - but it appropriates the qualities of something made by hand. On Grundtvigs Kirke every brick was laid one at a time by hand … is that one of the reasons that makes it such an amazing building?

Obviously the apartment building is a very very different type of building so is that voice of my inner puritan wrong and misplaced? Is it perfectly OK to use current technology to achieve some of the benefits for none of the skill or effort?

But Copenhagen has a long and well-established tradition using brick in its buildings and it’s not simply a practical solution simply because these new apartments are very tall blocks so traditional brickwork would not be appropriate …. just look at the huge power stations in the city from the 1930s or some of the very large brick apartment buildings from the 1920s and 30s and you can see good traditional brickwork on very large buildings.

I guess in the end it comes down to thinking that the finished buildings look a bit mechanical because it’s all rather too flat and rather too regular. Presumably the developer would argue that the cost benefits outweigh any quibbles about trying to keep alive traditional building methods and they would probably tell you about 19th-century apartment buildings with thin walls a single brick thick where cold and condensation and noise were and are a serious problem.

So do cost and comfort always trump aesthetics and rapidly-disappearing craft skills?